Following the killing of Mahmood Al-Mabhouh is Dubai, allegedly by Israeli Mossad agents, some people are starting to ask whether political assassination is being made more difficult by the proliferation of everyday surveillance. The Washington Post argues that it is, and they give three other cases, including that of Alexandr Litvinenko in London in 2006. But there’s a number of reasons to think that this is a superficial argument.

However the obvious thing about all of these is that they were successful assassinations. They were not prevented by any surveillance technologies. In the Dubai case, the much-trumpeted new international passport regime did not uncover a relatively simple set of photo-swaps – and anyone who has talked to airport security will know how slapdash most ID checks really are. Litvinenko is as dead as Georgi Markov, famously killed by the Bulgarian secret service with a poisoned-tipped umbrella in London in 1978, and we still don’t really have a clear idea of what was actually going on in the Markov case despite some high-profile charges being laid.

Another thing is that there are several kinds of assassination: the first are those that are meant to be clearly noticed, so as to send a message to the followers or group associated with the deceased. Surveillance technologies, and particularly CCTV, help such causes by providing readily viewable pictures that contribute to a media PR-campaign that is as important as the killing itself. Mossad in this case, if it was Mossad, were hiding in plain sight – they weren’t really trying to do this in total secrecy. And, let’s not forget many of the operatives who carry out these kinds of actions are considered disposable and replaceable.

The second kind are those where the killers simply don’t care one way or the other what anyone else knows or thinks (as in most of the missile attacks by Israel on the compounds of Hamas leaders within Gaza or the 2002 killing of Qaed Senyan al-Harthi by a remote-controlled USAF drone in the Yemen). The third kind are those that are not meant to be seen as a killing, but are disguised as accidents – in most of those cases, we will never know: conspiracy theories swirl around many such suspicious events, and this fog of unknowing only helps further disguise those probably quite small number of truly fake accidents and discredits their investigation. One could argue that such secret killings may be affected by widespread surveillance, but those involved in such cases are far more careful and more likely to use methods to leverage or get around conventional surveillance techniques.

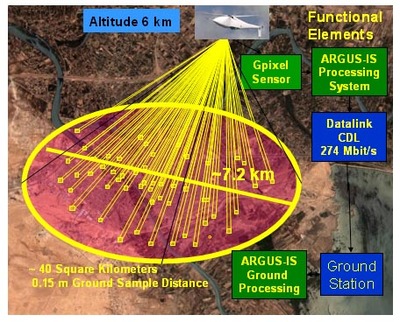

Then of course, there is the fact that the techniques of assassination are becoming more high-tech and powerful too. The use of remote-control drones as in the al-Harthi case is now commonplace for the US military in Afghanistan and Pakistan, indeed the CIA chief, Leon Panetta, last year described UAVs as “the only game in town for stopping Al-Qaeda.” And now there are many more nations equipping themselves with UAVs – which, of course, can be both surveillance devices and weapons platforms. Just the other day, Israel announced the world’s largest drone – the Eltan from Heron Industries, which can apparently fly for 20 hours non-stop. India has already agreed to buy drones from the same company. And, even local police forces in many cities are now investing in micro-UAVs (MAVs): there’s plenty of potential for such devices to be weaponized – and modelled after (or disguised as) birds or animals too.

Finally, assassinations were not that common anyway, so it’s hard to see any statistically significant downward trends. If anything, if one considers many of the uses of drones and precision-targeted missile strikes on the leaders of terrorist and rebel groups as ‘assassinations’, then they may be increasing in number rather than declining, albeit more confined to those with wealth and resources…

(Thanks to Aaron Martin for pointing me to The Washington Post article)