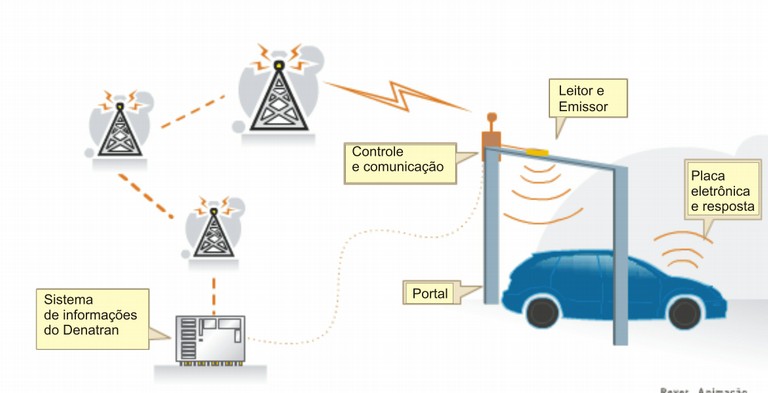

One of the items reported on in Privacy International´s assessment of privacy in Brazil was that ¨in November 2006, the Brazilian National Road Traffic Council approved a Resolution adopting a Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tags in all licensed vehicles across the country.¨ The Conselho Nacional de Trânsito (CONTRAN) is part of the Departemento Nacional de Trânsito (DENATRAN), itself part of the massive new Ministério das Cidades (Ministry of Cities), the product of Lula´s major ministerial reforms designed to shift emphasis and power away from the large rural landowners to the growing numbers of increasingly populous cities.

The new scheme is called the Sistema Nacional de Identificação Automática de Veículos (SINIAV, or National System for the Automatic Identification of Vehicles). Basically it will put an RFID-tag in every vehicle license plate, in a gradual process. Much like the new ID scheme for people, SINIAV is based on a unique number. In Annex II, Paragraph 3, the resolution provides a breakdown of exactly what will be contained in the tiny 1024-bit chip as follows. The unique serial number (64), and a manufacturer´s code (32), will be programmed in at the factory, leaving a total of 928 programmable bits. The programmable area contains two main sections. The first contains all the personal and vehicular information: place of registration (32), registration number of seller (32) application ate (16), license plate number (88), chassis number (128), vehicle tax number (RENAVAM) (36), vehicle make and model code (16) and finally 164 bits for ´governmental applications´. The remaining 384 bits are split into 6 blocks for unamed ´private initiatives.´

The new scheme is called the Sistema Nacional de Identificação Automática de Veículos (SINIAV, or National System for the Automatic Identification of Vehicles). Basically it will put an RFID-tag in every vehicle license plate, in a gradual process. Much like the new ID scheme for people, SINIAV is based on a unique number. In Annex II, Paragraph 3, the resolution provides a breakdown of exactly what will be contained in the tiny 1024-bit chip as follows. The unique serial number (64), and a manufacturer´s code (32), will be programmed in at the factory, leaving a total of 928 programmable bits. The programmable area contains two main sections. The first contains all the personal and vehicular information: place of registration (32), registration number of seller (32) application ate (16), license plate number (88), chassis number (128), vehicle tax number (RENAVAM) (36), vehicle make and model code (16) and finally 164 bits for ´governmental applications´. The remaining 384 bits are split into 6 blocks for unamed ´private initiatives.´

Privacy International note that there is no more than a mention of conformity to constitutional rules on privacy (of which more later). However there is much more that is of concern here. The resolution claims that the data will be encrypted between plate and reader, but the technical specifications are not given to any level of detail (*though there is more information from the Interministerial Working Group on SINIAV, which I haven´t examined in any detail yet). We all know already how easy it is to clone RFID chips. This scheme is supposed to be about security for drivers, but it could easily result in the same kind of identity fraud and consequent necessity of disproving the assumption of guilt created by automated detection systems for car-drivers as for credit cardholders. Could you always prove that it wasn´t your car which was the gettaway vehicle in a robbery in Saõ Paulo, or you driving it, when your actual car was in a car park in Curitiba? Widespread cloning of chips would also render the whole system valueless to government.

Then there is the question of function creep. The chip has spare capacity, and assigned space for unamed functions, state and private. Brazil already has a system of state toll roads (pay-for-use highways), and these chips could certainly be used as part of an automated charging system. That might be very convenient. However what other functions could be thought up, and how might safeguards be built in? As I have already noted, Brazil has no body for protecting privacy or data/information rights so it would be very easy for new more intrusive functionality to be added.

Combining the problems of a movement towards automated fines or changes, and criminality, another major issue would be the one recently revealed in Italy, where a automated red-light camera system was found to have been fixed in order to generate income from fines for corrupt police and a multitude of others.

The final question of course is whether this will all happen as planned or at all. The system would supposedly be complete by 2011. I know of a trial scheme in Saõ Paulo, but on a quick (and very unscientific) straw poll of people who I encountered today at the university here in Curitiba, there is to be no-one who has an RFID license plate or knows someone who does, and there is practically zero awareness even amongst educated professionals. Like the National ID-card scheme, people just don´t think it will go to plan or timetable. That may however, just reflect a (middle-class) Brazilian view of the abilities of the state.

Still, as the Frost and Sullivan market assessment states, all of this turns Brazil into a ‘highly attractive market for RFID suppliers’ which was probably the main motivation and will be the only real outcome.

Last week I mentioned the approval of the biometric passports scheme by the European Parliament, and that there were several countries that planned to fingerprint children under the age of 12 despite the legal, ethical and technical problems with this.

Last week I mentioned the approval of the biometric passports scheme by the European Parliament, and that there were several countries that planned to fingerprint children under the age of 12 despite the legal, ethical and technical problems with this.