These are just some pictures of the neighbourhood. Off the main streets, it’s generally a decaying but still lively place, full of tiny shops, with a few hotels and a major specialism in motorbikes…

Category: Brazil

Finding my feet and losing my head in Sao Paulo

It is my firm belief, yet to be disproved, that any urbanist worthy of the name can find a decent bar within 24 hours of their arrival in any city on the world, and preferably less. Read Ernest Hemingway’s Paris: A Moveable Feast. It’s Chapter 1. No-one knew bars like Hemingway. In Sao Paulo, as in Paris even today, it would be impossible to fail this challenge. I found mine this evening right next to a more famous bar at the corner of Sao Joao and Ipiranga which has started to believe its own mythology and therefore lost everything that once made it a bar worth celebrating in song, and I settled in to watch and learn.

I’ve already got so used to joking with barmen and concierges about my poor Portuguese that it’s almost like an icebreaker. The bar was haphazard, white tiles, and giant freezers which got the beer down to an appreciably glacial degree of cool, decent salgados and two grades of chili source to accompany them (hot and really hot – no-one has the first choice, of course).

Bars are human sociality at their most basic, their most primate-like. I once worked on a zoological expedition studying monkeys in Kalimantan, and there is very little I’ve seen in bars that I haven’t seem being done by other primates (apart from the serving of cold beers, which explains most of what happens in bars that you don’t see in monkey groups). The forced-together bonhomie, the silence amongst the mostly male clientele as some particularly fine example of the female of the species walks by (and that happens an awful lot in Brazil), the arguments about sport and politics, the group-dominance by alpha-males – at least in the absence of any alpha-females – it’s all there and it’s all – excepting the beer and the salgados – monkey.

It makes one depressed and optimistic at the same time. You know that anywhere that humans go, somewhere in the universe, there’s going to be a bar just like this. And yet, it makes you wonder whether we will ever manage to solve the enigma of cities, a solution that will bring in those shadowy figures who lurk just beyond the reach of the bright lights of the bar – the stick-thin figure of the beggar-woman who passed me twice this evening, the guy selling lottery tickets at the last minute, the prostitutes and thieves who have been driven to these ends because of the city, because their existence and the existence of the city don’t quite seem to coincide in the same way, the same spacetime. There’s a reason good urbanists need to find a good bar. It isn’t always for the same reasons as everyone else.

Sao Paulo Surveillance and Security

Nor surprisingly there is very little surveillance in the area around the hotel, except the old fashioned kind and you better be sure that people are watching you from the little shops and street corners. However when you head down the Av. Sao Joao into the financial district, it’s a different story. I was cautious about taking obvious pictures of police and security guards, let alone the serious security inside the bank entrances (metal detectors, scanners, guards etc.) because I just don’t know what kind of trouble that would bring, but here’s a flavour.

Touchdown in Sao Paulo

The centre of Sao Paulo not a place for those who don’t like the scent of human beings together or being touched and jostled. The streets smell of piss and sweat and there are boys begging and running and men lying in boarded-up doorways or just on the sidewalks, with their dogs or without…

It’s hot and wet and I’m lying on a bed in a hotel which is a good 2 stars short of the 4 that it claims to have, in a neighbourhood in which the only stars you’ll see are if you’re lying in the gutter. And many are.

I’m sorry to go gonzo on y’all but on first impressions that is the way I will have to write it. Sao Paulo is the kind of city that seems to have that effect. I’ve only really come here to talk to a few social organisations and to see Rio’s great rival, but it’s hard to know what to make of it. Flying into Congohas, we cut through the low clouds to the spectacle of this endless sprawl of towers and factories and suburbs and favelas and highways thrown together with as little sense or plan as any place I’ve been in Asia. Like Tokyo or Mumbai it’s just too big to take in or apprehend even from the air, although you can’t avoid the scalar indicators of class divisions – both vertical and horizontal. The airport is one of those which has been drowned in this rising sea of humanity which makes the final descent pass with a feeling of rooftop-skimming alarm, which a slight sideways jolt on the infamously greasy runway surface – a plane skidded out of control here in July 2007, killing 187 people – does little to allay.

We make it safely down. As we are heading to the terminal I see my first helicopter, another reminder of the social extremes of this place where the super-rich just don’t let their feet be soiled by the streets any more and which has the largest private helicopter use outside of New York.A taxi to the centre – they tell me there aren’t any buses though I am sure there are, and I won’t be making that mistake again!. The highway that snakes deeper into the city is hemmed in with rotting stone and concrete and every space that hasn’t been walled off has been reclaimed and is packed tight with self-constructed dwellings in various stages from shack to house. Occasionally huge voids are opened up – precursors to a further gentrification, some new fortified tower condominium – and the archaeology of the city is laid bare: a splash of colonial colour, deco curves and the confident lines of Brazilian modernism, all cut neatly and disrespectfully for some tower block with a European name and not a hint of Indio or African heritage. Brazil might not be an overtly racist culture in many ways, but ‘whiteness’ remains the shade of aspiration…

Then a sharp left off the highway and we are in the old centre. The taxi driver knows the map but he doesn’t know the area, and out path is blocked by a Sunday market. I take a mental note – I’ll be back later. We get to the hotel, which pleasingly is not anything like the priggish image on the website and if it is ‘perfect for business’, it certainly doesn’t look like the kind of business you do with a briefcase… This turns out to be exactly what O Centro is all about. I get out and head back towards the market for a pastel com queijo and a cool caldo de cana com limao, and just to wander amongst the fruit and veg sellers. This place is much more obviously mixed than Curitiba. The faces of the vendors are a whole range of darker shades, the accents more varied, tougher and more incomprehensible!

The toughness isn’t just in the voices of the stallholders though. The is a brash, hard city. The centre of Sao Paulo not a place for those who don’t like the scent of human beings together or being touched and jostled. The streets smell of piss and sweat and there are boys begging and running and men lying in boarded-up doorways or just on the sidewalks, with their dogs or without. Sleeping, drunk, dead – who knows? The market is winding down, an at the ends of the street, amidst the sickly sweet decaying piles of vegetable leaves and squeezed sugarcane pulp, several middle-aged whores work the last few departing customers. They half-heartedly ask me if I want something. I just smile and politely say no thank-you very much, which seems to amuse them. I don’t suppose they get or expect much of that sort of interaction. This sets a theme. There are women working the car parks, women on the street, women trying to entice any likely-looking customers into a seedy-looking film theatre for ‘fantasia’. Turning a corner suddenly the street is full of younger men standing around with largely older guys passing by. It’s only after the second transvestite offers me something else that I realise I’ve entered another kind of business district, which happily filters into a much more ordinary a relaxed set of gay bars and pastelarias. There seems to be some kind of club open, with another very tall transvestite on the door, but the queue outside seems to be mostly teenagers. I’ve only been a few blocks and this isn’t even (apparently) the really lively part of SP…

Cutting back to the Praca da Republica, there’s another much bigger market winding down, this one more of a craft-type affair with lots of wiry men and women selling hats and carvings and a whole avenue of dealers in stones and minerals and, outside the entrance to the Metro, food stalls selling either Japanese yakisoba or cream cakes. Neither appeals, and as it looks like rain, I head into a bar. Sao Paulo against Botafogo is on the TV but not too loudly and no-one seems interested, the beer is cheap and the woman behind the bar is singing to herself so I stay and sip the cold lager and watch the rain come down and the passing beggars and freaks and drunks and I am thinking that I am just a few hundred yards from Parque da Luz where the city has installed public-space CCTV, and it might be the beer but just makes me want to laugh. It just seems so tiny, so pathetic a gesture, how can it possibly do anything to this roiling mass of humanity with its desires and suffering and joy and desperation.

I’ve touched down in Sao Paulo.

My plans

Today there probably won´t be that much new here as I am concentrating on preparing for interviews for the next two weeks in Saõ Paulo and Brasília. I will be talking to various NGOs (mainly concerned with urban violence and security), academics, parliamentarians and representatives for the federal police and government ministers. I am also meeting Danilo Doneda later today, who is the leading Brazilian legal expert on privacy and data protection, and a member of the Habeus Data network, which campaigns for information rights in Latin American.

(My netbook has also decided not to work today, so if I can´t get that fixed there might not be much here at all for the next two weeks! Why do these things always happen just when it is least convenient?)

Private Security in Brazil: the global versus the specific

One of the purposes of my project here is to differentiate what is the product of globalising forces (or indeed generator of such forces), and what is more specific and particular to each of the countries and cities that I am examining. If you skim Mike Davis and Daniel Bertrand Monk´s 2007 collection, Evil Paradises, you can certainly come away with the overall impression that everything bad in the world is down to neoliberal capitalism. But actually, many of the contributors to that book, particularly Tim Mitchell on the reasons why the state and private capital are so entangled in Egypt and Mike Davis himself on Dubai, are quite careful about describing the particular historical roots and contemporary developments that have led to the situations they observe. I am trying to do the same.

As I wrote last week, the private security industry here in Brazil is obvious and ubiquitous. It is easy to see this simply as part of a trend towards privatisation, and the growth of personal, community and class-based responses to risk and fear that is pretty much the same, or is at least in evidence, all over the world. However, there are several factors here that point internally and backwards in time. The first was made clear to me reading James Holston´s superb 2008 book Insurgent Citizenship, which is both an excellent ethnographic study of contemporary conflicts over housing and land in Saõ Paulo and an illuminating historical account of the roots of such conflicts in the development of citizenship, property rights and order in Brazil from its foundation.

As I wrote last week, the private security industry here in Brazil is obvious and ubiquitous. It is easy to see this simply as part of a trend towards privatisation, and the growth of personal, community and class-based responses to risk and fear that is pretty much the same, or is at least in evidence, all over the world. However, there are several factors here that point internally and backwards in time. The first was made clear to me reading James Holston´s superb 2008 book Insurgent Citizenship, which is both an excellent ethnographic study of contemporary conflicts over housing and land in Saõ Paulo and an illuminating historical account of the roots of such conflicts in the development of citizenship, property rights and order in Brazil from its foundation.

Holston makes a comparison between the foundation of Brazil and the other, and in many ways superficially similar, federal state in the Americas, the USA. He argues that whilst the USA consolidated itself within a smaller territory before expanding west, Brazil arrived as a massive fully-formed state. In consequence, the USA developed a form of governance that expanded with the territory, and this included centrally-determined land surveying and an emphasis on small townships to control territory and organise development. Brazil on the other hand, being basically divided between highly administered colonial towns and practically no administration at all elsewhere, had ´an incapacity to consolidate itself´ (65). The state therefore depended on large landowners, and in particular after the creation of the National Guard (1831), which was delegated to these property owners, these landowners also acquired a military-police power. Effectively, this conflation of private interest and the law, or coronelismo, was built into the governing structure and culture of Brazil.

It is a masterly analysis but Holston´s one slight error, I think, is to call this ´a nationwide privatisation of the public´ (66). It is hard to argue this when the public had never really yet existed in anything like the idealised sense in which it is used by political scientists – in other words the nature of the ´public´ in Brazil was always pre-defined by the private, and by the power of the private, rather than the other way around. In other words, what has happened since, off and on, has been a struggle by the more democratic and progressive interests in Brazil to bring the private into the public. You can see this right up to the present day with the struggles by the state to prohibit and eradicate the so-called Autodefesas Comunitárias, the authoritarian paramilitary groups that have emerged in Rio and other cities in recent years. The struggle is essentially one of creating the ´public´.

The ADC issue highlights another historical reason for the dependence on and trust in, private security in Brazil. The reason is simply that the law is not trusted. Judges and courts have long been perceived as essentially tools of privilege and the official police in their various forms are not trusted by many people of all social classes. The former, as with coronelismo, goes way back into the post-colonial period, but the latter is also a particular legacy of the dictatorships (which can also be seen as the ultimate private control of the public), the last of which only ended in 1985. This leaves Lula´s government, the first that can really claim to be at all progressive, with several major problems: making an untrusted police more trustworthy whilst at the same time increasing their effectiveness and equipment; regulating the thousands of private security firms and, if possible, reducing the dependence of property-owning Brazilians upon them; and finally, and most importantly, dealing with the massive underlying inequalities, that are also a product of what Holston calls the the inclusive but inegalitarian nature of Brazil´s constitution and subsequent socio-economic development. The latter subject is outside the scope of my project, but I will be continuing to delve into the differentiations and intersections between segurança pública and segurança privada whilst I am here.

Surveillance, Security and Social Control in Latin American symposium

Transport Surveillance in Brazil (1) SINIAV

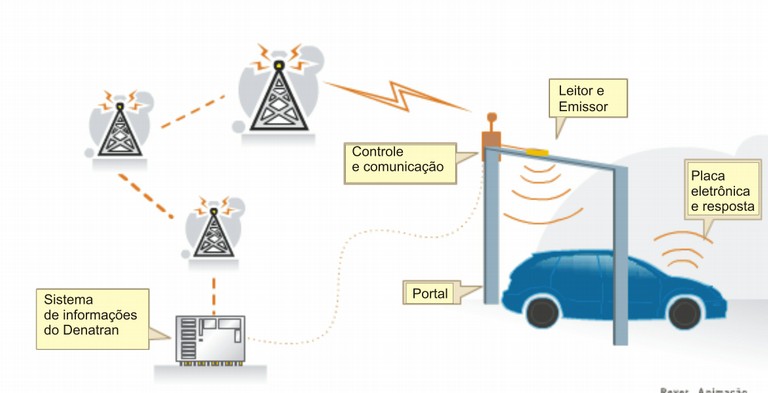

One of the items reported on in Privacy International´s assessment of privacy in Brazil was that ¨in November 2006, the Brazilian National Road Traffic Council approved a Resolution adopting a Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tags in all licensed vehicles across the country.¨ The Conselho Nacional de Trânsito (CONTRAN) is part of the Departemento Nacional de Trânsito (DENATRAN), itself part of the massive new Ministério das Cidades (Ministry of Cities), the product of Lula´s major ministerial reforms designed to shift emphasis and power away from the large rural landowners to the growing numbers of increasingly populous cities.

The new scheme is called the Sistema Nacional de Identificação Automática de Veículos (SINIAV, or National System for the Automatic Identification of Vehicles). Basically it will put an RFID-tag in every vehicle license plate, in a gradual process. Much like the new ID scheme for people, SINIAV is based on a unique number. In Annex II, Paragraph 3, the resolution provides a breakdown of exactly what will be contained in the tiny 1024-bit chip as follows. The unique serial number (64), and a manufacturer´s code (32), will be programmed in at the factory, leaving a total of 928 programmable bits. The programmable area contains two main sections. The first contains all the personal and vehicular information: place of registration (32), registration number of seller (32) application ate (16), license plate number (88), chassis number (128), vehicle tax number (RENAVAM) (36), vehicle make and model code (16) and finally 164 bits for ´governmental applications´. The remaining 384 bits are split into 6 blocks for unamed ´private initiatives.´

The new scheme is called the Sistema Nacional de Identificação Automática de Veículos (SINIAV, or National System for the Automatic Identification of Vehicles). Basically it will put an RFID-tag in every vehicle license plate, in a gradual process. Much like the new ID scheme for people, SINIAV is based on a unique number. In Annex II, Paragraph 3, the resolution provides a breakdown of exactly what will be contained in the tiny 1024-bit chip as follows. The unique serial number (64), and a manufacturer´s code (32), will be programmed in at the factory, leaving a total of 928 programmable bits. The programmable area contains two main sections. The first contains all the personal and vehicular information: place of registration (32), registration number of seller (32) application ate (16), license plate number (88), chassis number (128), vehicle tax number (RENAVAM) (36), vehicle make and model code (16) and finally 164 bits for ´governmental applications´. The remaining 384 bits are split into 6 blocks for unamed ´private initiatives.´

Privacy International note that there is no more than a mention of conformity to constitutional rules on privacy (of which more later). However there is much more that is of concern here. The resolution claims that the data will be encrypted between plate and reader, but the technical specifications are not given to any level of detail (*though there is more information from the Interministerial Working Group on SINIAV, which I haven´t examined in any detail yet). We all know already how easy it is to clone RFID chips. This scheme is supposed to be about security for drivers, but it could easily result in the same kind of identity fraud and consequent necessity of disproving the assumption of guilt created by automated detection systems for car-drivers as for credit cardholders. Could you always prove that it wasn´t your car which was the gettaway vehicle in a robbery in Saõ Paulo, or you driving it, when your actual car was in a car park in Curitiba? Widespread cloning of chips would also render the whole system valueless to government.

Then there is the question of function creep. The chip has spare capacity, and assigned space for unamed functions, state and private. Brazil already has a system of state toll roads (pay-for-use highways), and these chips could certainly be used as part of an automated charging system. That might be very convenient. However what other functions could be thought up, and how might safeguards be built in? As I have already noted, Brazil has no body for protecting privacy or data/information rights so it would be very easy for new more intrusive functionality to be added.

Combining the problems of a movement towards automated fines or changes, and criminality, another major issue would be the one recently revealed in Italy, where a automated red-light camera system was found to have been fixed in order to generate income from fines for corrupt police and a multitude of others.

The final question of course is whether this will all happen as planned or at all. The system would supposedly be complete by 2011. I know of a trial scheme in Saõ Paulo, but on a quick (and very unscientific) straw poll of people who I encountered today at the university here in Curitiba, there is to be no-one who has an RFID license plate or knows someone who does, and there is practically zero awareness even amongst educated professionals. Like the National ID-card scheme, people just don´t think it will go to plan or timetable. That may however, just reflect a (middle-class) Brazilian view of the abilities of the state.

Still, as the Frost and Sullivan market assessment states, all of this turns Brazil into a ‘highly attractive market for RFID suppliers’ which was probably the main motivation and will be the only real outcome.

Brazil as surveillance society? Privacy International´s view (1)

Every year, Privacy International publishes a kind of index of privacy. The methodology is qualitative and has a strong element of subjectivity based on PI´s campaigning objectives (for example my colleague, Minas Samatas, finds their assessment of Greece as the best country in Europe in this regard, ludicrous). There are also problems with the equivalence of the all the different categories, both in terms of whether all the surveillance identified is even ethically ´bad´ anyway, and in the adding up of categories to conclude that you can lump together the USA, UK, Russia and China. However, it remains a good focus for discussion and no-one else does anything similar.

Let´s see what they concluded about Brazil. Brazil ends up in the 3rd worst category overall, with a ´systematic failure to uphold safeguards´. In particular, PI condemned:

- the role of the courts in weakening constitutional rights of data protection (something I will be coming back to next week);

- the lack of a privacy law;

- the lack of habeus data provisions;

- the lack of a regulatory of personal data and privacy;

- an overly simplistic test for the legailty of communications interception;

- the new ID law;

- recent Youtube censorship;

- increasing workplace surveillance, which has only been partially addressed by the courts;

- widepsread private interception of intenet and e-mail traffic;

- that fact that ISPs are required to keep and hand over traffic data to police;

- the extensive road transport surveillance using RFID.

However they also noted:

- the protection of the right to privacy of children under a 1990 law; and

- the fact that bank records are protected under the constitution, and warrants are required to seize them

I will be going through their country in report in more detail next week and using this as one of the bases for the questions I will ask NGO representatives and parliamentarians in the weeks after wards.

Brazil as Surveillance Society? (1) Bolsa Família

The claim that Brazil is a surveillance society, or at least uses surveillance in the same fundamental organising way as the UK or Japan does, is based on the bureaucracy of identification around entitlement and taxation, rather than policing and security.

My previous post on the subject of whether Brazil was a surveillance society put one side of an argument I am having with myself and colleagues here: that the use surveillance in Brazil is fundamentally based on individual (and indeed commodified and largely class-based) security, rather than surveillance as fundamental social organising principle (as one might legitimately claim is the case in Britain). Now, I deliberately overstated my case and, even as I was posting, my argument was being contradicted by colleagues in the same room!

So here´s the counter-argument – or at least a significant adjustment to the argument. In most nation-states, entering into a relationship with the state involves forms of surveillance by the state of the person. This relationship is more or less voluntary depending on the state and on the subject of the relationship. In most advanced liberal democracies, the nature of surveillance is based on the nature of citizenship, particularly:

- the ability of citizens to establish claims to entitlement, the most fundamental to most being a recourse to the law (to protect person and property), secondly the ability to case a vote, and more something that is generally more recent in most states, the right to some kind of support from the state (educational, medical, or financial);

- the ability of the state to acquire funds from citizens through direct or indirect taxation, to support the entitlements of citizens, and to maintain order.

I am not going to consider law and order, or indeed electoral systems, here but rather I will concentrate on the way that surveillance operates in an area I had previously begun to consider: the bureaucracy of identification around state-citizen relations particularly in the areas of entitlement and taxation. The claim that Brazil is a surveillance society, or at least uses surveillance in the same fundamental organising way as the UK or Japan does, is based on this rather than policing and security.

There are two broad aspects: on the one side, taxation, and on the other, entitlement. I´ll deal first with the latter (which I know less about at the moment), in particular in the form of Lula´s Programa Bolsa Família (PBF, or Family Grant Program), one of the cornerstones of the socially progressive politics of the current Brazilian government. The PBF provides a very simple, small but direct payment to families with children, for each child, provided that the children go to school and have medical check-ups.

Of course these requirements in themselves involve forms of surveillance, through the monitoring of school attendance by children – for which there is a particular sub-program of the PBF called Projeto Presença (Project Presence) with its own reporting systems – and epidemiology and surveillance of nutrition through the Ministério de Saúde (Ministry of Health). However underlying the entitlement is massive compulsory collection of personal information through the Cadastro Único para Programas Sociais (CadÚnico, or Single Register for Social Programs), set up by Lula´s first administration to unify the previous multiple, often contradictory and difficult to administer number of social programs. This is, of course a database system, which as the CadÚnico website states, ¨funciona como um instrumento de identificação e caracterização socioeconômica das famílias brasileiras¨ (¨functions as an means of identification and socioeconomic caracterization of Brazilian families¨). Like most Brazilian state financial systems, CadÚnico is operated through the federal bank, the Caixa Econômica Federal (CAIXA). The CadÚnico database is founded on ¨um número de identificação social (NIS) de caráter único, pessoal e intransferível¨ (¨a unique, personal and non-transferable Social Identification Number or NIS¨). I am unclear yet how this NIS will relate to the new unique identification system for all citizens.

Entitlement is demonstrated with (yet another!) card, the patriotic yellow and green Cartão PBF. Like the CPF card, this is a magnetic strip card rather than a smart card, and is required for all transactions involving the PBF. Also like the CPF, but unlike many other forms of Brazilian ID, it has nothing more than the name of the recipient and the CadÚnico number printed on it. In this case the recipient is generally the mother of the children being claimed for, a progressive and practical measure shared with other family entitlement programs in Brazil.

The PBF card in itself may not be enough to claim as you would still need at least the Registro Geral (national ID) card to prove that you are the named holder of the PBF card. The card itself may be simply designed to generate a sense of inclusion, as the pictures of happy smiling PBF cardholders on the government websites show consistently emphasise, although of course, like so many other markers of entitlement to state support, it could also become a stigma.

The information collection to prove entitlement is quite extensive, and here I have translated roughly from the website:

- house characteristics (number of rooms; construction type; water, sewerage and garbage systems);

- family composition (number of members, dependents like children, the elderly, those with physical handicaps);

- identification and civil documents of each family member;

- educational qualification of each family member;

- professional qualifications and employment situation;

- income; and

- family outgoing (rent, transport, food and others).

Although PBF is a Federal program, the information is collected at the level of individual municipalities, and there is thus the potential for errors, differences in collection methods, delays and so on to hamper the correct distribution of the money. So each municipality is required to have a committee called the Instância de Controle Social (Social Control Authority) which, whilst it may sound sinister to anglophone ears, actually refers to the control of civil society over the way that the government carries out its social programs. This is also quite a lot of information of the most personal kind and whilst, unlike in many countries there is no central authority of Commissioner for Data Protection in Brazil, there is particularly for PDF, an Observatório de Boas Práticas na Gestão do Programa Bolsa Família (Observatory for Best Practice in the Management of the PBF), which has a whole raft of measures to safeguard and protect the data, correct errors etc (what has been called habeus data principles). Effectively, this is a case of knowing exactly quis custodis ipsos custodes!

Now of course, such a large database of information about the most vulnerable people in society has the potential to be misused by a less progressive or even fascist government. Marxist analysis of early welfare systems has tended to colour our views of such programs as being solely about the management of labour on behalf of capital and the control of the working classes by the state to prevent them from more revolutionary action. For more recent times in Surveillance Studies, John Gilliom´s book, Overseers of the Poor, showed how much Federal assistance programs in the USA could impact negatively upon the lives of claimants, particularly women, in the Appalachian region, and revealed the everyday forms of resistance and adaptation that such women used to make the programs function better for them. I will have to examine more detailed anthropological studies of the PBF to see whether similar things are true of the Brazilian program. I don´t want to get too much into the effectiveness of this program now, although I am trying to examine the correlation of the PBF with apparently declining crime rates in Brazilian cities, but it is worth noting that the World Bank rates it as one of the most successful ways of dealing with extreme poverty in the world. As a general observation, it does seem that only those who object to redistributive policies full stop (or just dislike Lula himself) or those who think it does not go far enough, have any serious complaint about the PBF. But there is far more to consider here…